Epidemics as a critique of science

The main premise of the movie is the resistance of a dozen men against an uncontrollable infection, so you could say that the theme of epidemics is essential to it, if not dominant. Actually, it’s almost reason enough for the story to be contemporaneous and set in an isolated station in Antarctica. It enables the screenwriter to develop and control what’s happening inside a small place, focusing on the propagation of the Thing from man to man, while maintaining a very realistic environment. Were the action set in a less plausible place, such a threat probably would not have worked that well. For example a futuristic spaceship was a good way for Ridley Scott to provide a few thrills to the audience with his Alien (released 3 years earlier), but when your own monster is something of a shapeless, invisible virus, you better try to anchor your story in a more relatable environment if you want people to believe in the Thing and get scared at its ‘powers’ –which are essentially those of an aggressive, day-to-day sickness, when you put graphical considerations aside.

Before we comment on the role of scientists, let’s briefly state what the common man fears most about an epidemic. First, it’s almost impossible to protect yourself from the propagation, for the spreading is so fast and the pathogen so young that no one has found a vaccine yet. Furthermore, detection is rendered difficult for the same reasons, so you can never be sure whether it’s safe of not to keep close with people –even your friends. In the end you could get physically affected, to the point that you might have a hard time recognizing yourself. This partial loss of identity sometimes culminates in an untimely death. These features are of course emphasized in the movie, but the point is that these elementary fears inhabit everyone.

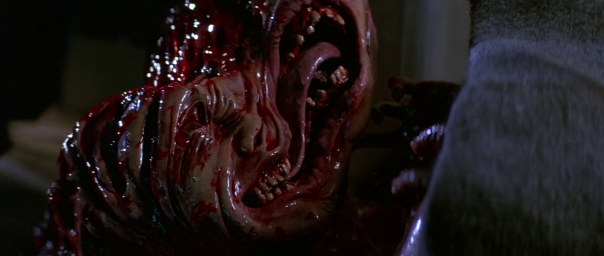

One of the strengths of the movie, and a valuable contribution from master of horror John Carpenter, was to trigger these deep terrors while fascinating us at the same time. The frame above belongs to the scene where the Americans discover the infected dog in the kennel. They retain speechless, devastated stares for a few elongated seconds; on their following shot they’re immediately holding guns and shooting at the creature, as if they were first amazed at the transformation but then would reject it most violently. It’s some kind of love/hate relationship that the everyday man do maintain with science, amazed at the wonders it opens up to, yet afraid to leave his marks and the comfort of more traditional values.

Scientists may tend to forget about the second part, but about half of the research station population has little to insignificant scientific knowledge (or so it seems): aside from chopper pilot MacReady, there is a cook, a dog trainer, a security guy… Even among the others you can’t really tell what kind of research they were doing before the beginning of the events, you just see them playing computer chess or table tennis so it’s rather easy for everybody to connect with most of the characters. MacReady calmly spills his drink into the computer after he loses a game, he may act violently but always in its own rational way and he survives to the end of the movie; on the other hand the biologist Blair quickly panics and wreaks havoc in the radiocommunications room, and the other man who finds pride or humor (camera and acting make it impossible to tell!) in the discovery of the disfigured corpse will ironically become the first human victim seen in the movie. Carpenter and his team succeed in showing realistic and relatable characters, while conveying an image of scientists who lack pragmatism, sometimes dismissing too quickly the consequences of their acts.

_Can’t burn the find of the century. That’s gonna win somebody the Nobel prize!’

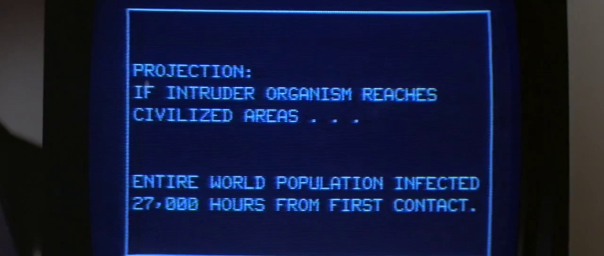

Let’s get back to the Thing and see why it’s even more than your standard epidemic. Obviously it’s lethal and could threaten the whole planet, that’s what Blair’s computer tells us (in one of the rare displays of research technology of the movie) and what you can feel in your guts anyway. But what’s really frightening is that the Thing seems to have a will of its own. When speaking about a normal virus, you’d say that it needs to infect hosts in order to survive. But the Thing seems to want to be lethal, it wants to propagate outside the station and infect the whole humanity. Much like in an anticipated version of what would be later called ‘the gray goo scenario’, it’s ready to absorb and fill everything at the same time, and it badly wants to do so. It tries to hide among everybody, and when it realizes it doesn’t work it changes its strategy and tries to return to a cryogenic state. It reflects our fear to encounter, or rather create, something which would outsmart us and take control over us -an underlying theme to science-fiction nearly as old as the first robots on screen.

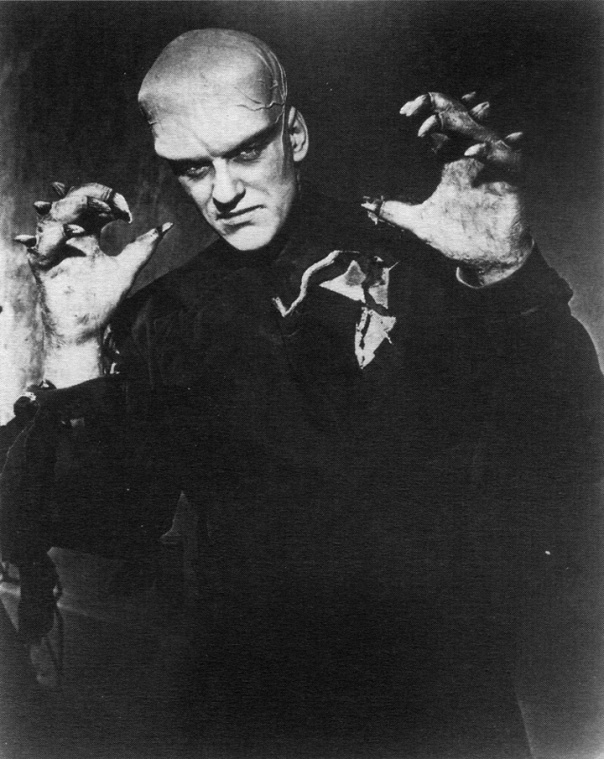

A scientific theme closely related to epidemics, genetics are a side concern expressed through the functioning and -more strikingly- the appearance of the Thing. As if its way of reproducing was not worrying enough (intruder cell controlling the outside of the host and camouflaging inside), the Thing reveals itself with grotesque, yet still horrifying modifications from well-known organisms (dog or man). David Cronenberg’s The Fly would be released 4 years later with similar biological concerns. For the last years tissue engineering has been booming, and we’re trying to grow limbs inside laboratories, so once again science-fiction proved to be just ahead of its time. In the first adaptation of the novella Who Goes There? in 1951 titled The Thing from Another World, the Thing was sort of a plant/human creature, as shown below. Carpenter’s choice of an invisible, omnipresent threat is yet another proof that the genre uses current issues to induce fear and provoke thoughts among the audience.

In the end, fire seems to be the only answer to the spreading of the Thing. The only remaining one, but also the only effective one, as the Thing can easily survive below-zero temperatures, and isn’t really affected by dismemberment/partitioning. Two colors detach themselves from the lot and fight for dominance: the eerie blue from the night lights outside, which progressively invades the research station, and the aggressive yellow-orange from the flamethrower and the explosions, which destroys everything it touches and wins at the end of the movie, as the whole facility burns. It looks like mankind should have stopped technology after this ‘first invention’, for fire is powerful enough to rule out any problem here, and already quite dangerous in itself. It provides a way to survive both the cold and the Thing. Yet we asked for more, invented more, and tripped on ethical dilemmas… Do we deserve the accidents brought upon us by technology? Is it presumptuous to keep searching for new science instead of settling for what we already have?