The threat of alien life

The main reason why The Thing did not perform well at the box-office in spite of its significant budget (more than Alien, slightly less than Aliens) and its obvious value (which was to be recognized later) is probably to be found in the conceptual aspect of the enemy, invisible yet ubiquitous and unstoppable. Today still, few producers would dare to envision a movie based on a shapeless monster. Furthermore, Spielberg’s E.T. was released two weeks earlier, and the audience probably remembered Ellen Ripley’s ordeal enough not to wish going through such a disturbing experience once again, so they chose the family-friendly film over what claimed to be ‘the ultimate in alien terror’.

To make things even more subtle, the origin story of the Thing is only alluded to in a small number of scenes, and it is never directly seen as using alien technology: the massive spaceship has been emptied about 100,000 years before being visited by the Americans, the ice block has already been carved when they arrive at the Norwegian facility, even Blair has disappeared when they discover the escape spacecraft being constructed under the tool shed -with the only violet lighting of the movie, so as to emphasize the out-of-our-world, unrelatable dimension of the Thing.

Characters are left with absolutely no possibility to communicate with it; it flees dialogue and avoids confrontation up until it’s been exposed, eventually attacking or screaming with intensity as if it weirdly wished to state its own existence (or so I interpreted my feeling that such a message could not be met with any comparable answer from the humans). In the end it leaves us with facing an organism bent on survival, at least as much intelligent as ourselves, but we cannot tolerate any identification to it. However -and that’s the point to introducing extraterrestrial lives here and in many other SF movies- who’s to say that our behavior would not be met with the same incomprehension if we were to find ourselves in a similarly isolated and hostile situation? Who’s to say our deepest instincts do not meet with the Thing’s motives?

Science perverting human relationships

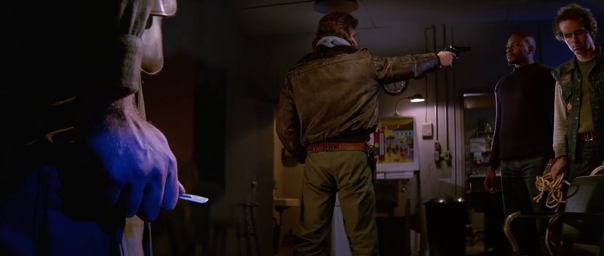

Now let’s take a look at the frame above. The unfolding of the scene and the way it’s been shot actually relates to our last interrogations, revealing that the director was clearly conscious of the underlying stakes here and making The Thing more laudable than the usual, first degree alien invasion movie. Using the gun as a threat, MacReady wants each of his teammates to tie themselves with a rope in order to make them go through the copper wire detection test. Clark quietly draws a scalpel but is immediately shot back upon attacking MacReady. Clark, the dog trainer, actually seemed like the most sensitive man of the team; you never could have guessed that pressure would build to the point that he would try to slash someone else with a blade. The close-up on his purple-blue lit hand could be interpreted as an influence from the Thing, but we later learn that he was indeed still human, so the lighting actually suggests that deep inside he is inhabited by instincts similar to what moves the Thing. Besides, his face remains hidden out of the screen, as a further suggestion of identity loss: he answers to a primitive survival call and yearns for a proud and naive independence he believes he could obtain thanks to the sharp blade. But technology is only a lure here, bringing no better outcome than violence and death.

A few tools are repeatedly used throughout the film (computers, fuses, helicopter…), out of which guns and flamethrowers are the most shown and the most hurtful. They induce imbalance in relationships, which become tainted with power and fear. The arrival of the Thing is just the starting point of the ‘Nobody trusts anybody now’ that MacReady records in his vocal journal, with uncertainty and shame -yet another interesting detail, he rewinds the journal and records something else over this symbolically painful assertion. Much of the tension actually ensues, not from the prospect of facing the Thing, but rather from the impossibility to hold together a group filled with defiance. Technology becomes an obstacle when it can infect and hide inside people (to be related with the epidemics and biological issue previously raised), but mostly because people are willing to adopt it and let it invade their lives, ignoring the share of social stirring which comes with it.

Questioning ‘human nature’

The Thing eventually raises the question of what it means to be human. Much like in Blade Runner with Rachael and Deckard’s journey to realize they’re replicants, the events surrounding the Americans progressively cast some doubt over their initial certitude to belong to mankind. Unexpected transformations of their friends act as catalysts to their self-alienation. They cannot be sure not to host the Thing, for they know that an infected man would act just like any other man and spontaneously wish not to be under the influence of the intruder organism. This is obvious in the copper wire scene, where most of the tested ones express agitation before the test, and then respond with either relief or anger that their humanness has been challenged. According to the story, free will and individuality are characteristic claims, but they can be replicated and do not suffice to define a man.

I would say that characters are most humans when they express some vulnerability, to the point of endangering their own lives. When the station commander comes under suspicion and suggests to give away his gun, you get the feeling that he’s probably not infected. Same thing for the guy who tells he’s not ‘up to it’ when asked to become in charge of security. On the contrary, Childs jumps on the possibility to gain control and makes himself a suspect to the audience. This unwillingness to assume power may culminate in a suicide attempt, with the dead man found in the Norwegian facility, or Blair who tried to hang himself in the tool shed but was turned by the Thing before he could succeed in saving his individuality, his dignity. Thus, instead of knowledge or technological superiority, vulnerability and the acknowledgement of one’s own imperfections might be the most revealing tokens of humanity.

The end of this commentary will parallel the last sequence of the film. Exhausted and disarmed, MacReady (whom we’re sure he’s not been infected) is rejoined by Childs, whose disappearance for the last 15 minutes or so is quite suspicious and not reassuring at all. At the same time he can’t be sure like us that MacReady hasn’t become a host, so we should not be prejudiced against someone because we do not know everything about this person. In the closing seconds the two of them share a bottle of scotch in a symbolical rebirth of society. The point is, whether you’ve been infected or not, whether it’s true, false, or merely subjective to say that you’ve been subverted by science and technology, you have to offer your trust somewhat blindly in order to maintain a community.